Ed McCormack (New York

Art Reviews

Controversial Australian painting

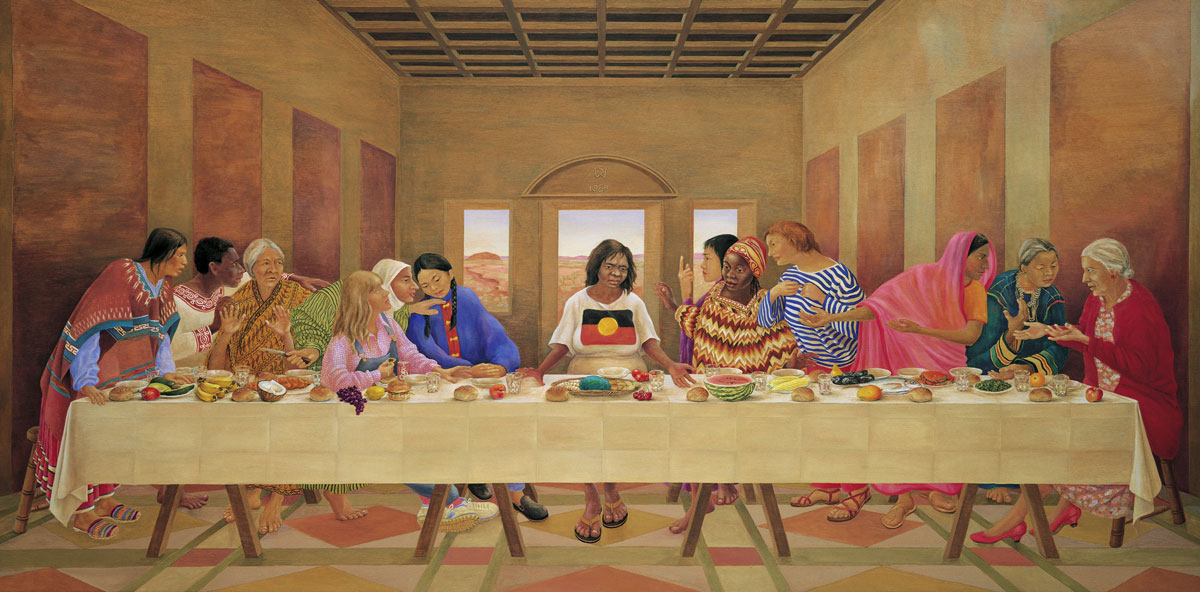

The centre-point of her exhibition was a large work called The First Supper, which caused a great deal of controversy when it was first shown in Australia. It consists of thirteen female figures posed as Leonardo da Vinci's Last Supper, with the Christ figure represented by an Aboriginal woman wearing a T-shirt adorned with the red, black, and gold Australian Aboriginal flag.

I asked Ms. White why she'd made the painting in this form.

Susan Dorothea White (SDW): Essentially, I did this painting for the Australian Bicentennial in 1988. It's a reversal of Leonardo's painting in every way, because they're all women instead of men, and the Leonardo has faces which are all very similar, except that some have grey hair, and Judas is dark. So I reversed everything and represented women from all different parts of the world, because in Australia we are a very multicultural society. And instead of a money purse in Judas' hand, Judas holds an Aboriginal dilly-bag, and whereas all the other women are eating bread-buns and have glasses of water, Judas has a hamburger and a Coca-Cola. And on the table I had a lot of fun, with food from every part of the world. I did a lot of research into the origins of fruits and vegetables.

NG: This painting caused quite a controversy when it was first shown in Australia because it was entered in a religious art exhibition.

SDW: Yes, it's a prize for religious art called The Blake Prize. It [the painting] was called by the critics, "a most excruciating piece of kitsch", which delighted me no end, because it is very good publicity and [because] the heading of his article was "Ludicrous Leonardo". And I thoroughly agree with him because...

NG: It's exactly what it is.

SDW: Yes. The idea of having thirteen figures on one side of a table is absolutely ridiculous. But it is a great – Leonardo's painting, of course – a great painting and it's a marvellous composition, and I learnt a tremendous amount by copying this. I actually copied the composition exactly, using a calculator so that the hands and heads and everything is exactly in proportion to his painting. And I just changed the faces and, of course, I experimented on the table and added a lot of different foods.

NG: It's quite a large work; it's more than two and a half metres long.

SDW: That's right.

NG: What about here in Europe? Was it also controversial when shown in Amsterdam and Cologne?

SDW: No. I found people really understood it. And people of all ages, from young teenagers through to really old people. And we had a colour poster made, and that is selling very well at the exhibition in Cologne.

NG: Now after the Cologne exhibition ends, the work goes on to Munich, I believe, and it will be shown permanently there.

SDW: Yes. A private person bought the painting. She said she would buy the painting on the condition that a public building could be found to display it; and she found that the Volkhochschule in Munich was willing to exhibit the painting, so that's where it will be.

NG: Your work seems to be more popular here in Europe than it is in Australia. Have you ever wondered why? You must have.

SDW: Yes, well everybody says that you're not appreciated in your own country. But I think there's more to it than that. I think it's because people in Europe, particularly in Germany, like to discuss a work and they like something to actually say something about life. And my subject matter is about people and human situations. A lot of it is to do with human rights issues. For instance, my woodcut Cry Freedom has been inspired by the struggle of black people in South Africa for equality, and the central figure is a female, and she is surrounded by oppression, with batons and boots and everything coming in around her in a circle. But she is very positive. She's looking up and out – her hands are facing out. I've also used this same theme in my sculpture – a sandstone carving of a woman – called Woman Oppressed – she's not an oppressed woman, she's a woman oppressed, but she's looking up and facing out. She's also torso-less, and this is my reaction to the kinds of ways you see women depicted, without heads and arms – they're just bodies. So I thought I'd make a sculpture of a woman without a torso. Her feet are huge, to contradict the idea that women should have small feet, which is part of our culture: Cinderella had tiny feet, and the Chinese bound women's feet. So it's a protest against these social stigmas.

NG: After the exhibition in Cologne closes, you then return to Australia, and your work, and then you're coming back here. You have an exhibition coming up in Holland again next year.

SDW: Yes, in The Hague. I'm not sure exactly when, but it will depend on when I'm able to produce enough work for the exhibition, too.

NG: That's rather important, too, because you said sometimes you spend quite a lot of time – The First Supper – you spent two years working on that?

SDW: Yes, well that took two years. But that also means that I have work that is in progress. Already, back in Sydney, I have several sculptures, and several prints towards completion, and one important painting which I've been working on for over a year, called The Seven Deadly Isms.

NG: That may be the centrepiece for the next exhibition?

SDW: Yes, that will be like The First Supper.

NG: Let's hope it's just as controversial. We look forward to it. Thank you for talking to us. And great success on your return. Her new work, of course, is based on Hieronymus Bosch's painting The Seven Deadly Sins. Painter Susan White, whose exhibition can be seen at the moment at Galerie am Buttermarkt in Cologne, Germany. Later the central work The First Supper will be permanently housed in Munich in the Volkhochschule's gallery.

Images, Radio Netherlands Worldwide, Apr. 1991